At 06:00 UTC on the 22nd of September 2016 the surface analysis chart for the North Atlantic showed Tropical Storm Lisa west of the Cape Verde Islands already north of twenty degrees latitude and tracking well to the north, no threat to the Caribbean. Tropical Depression Karl was several degrees north of the Lesser Antilles, also tracking north of west. There were no features threatening us. Over Africa, over central Mauritania about five degrees west of Timbuktu, was a 1010mb low that I didn’t even notice at the time. My interest was in the forty degrees of longitude, the twenty-four hundred nautical miles of warm tropical waters between the Cape Verde Islands and the Lesser Antilles – particularly during this part of hurricane season when the Cape Verde class hurricanes happen. Storms like, say, Ivan the Terrible in 2004, which wiped out half the fleet in Grenada (which was only the beginning of that storm's rampage).

Two days later, 24 September, the surface analysis chart showed a tropical wave stretching south from the Cape Verde Islands. Paul O’Regan of Carriacou’s Technical Marine Management said there was also a low associated with the wave and that it was moving fast – 25 knots (typical is 10 to 15 knots) – and was expected to develop. Fast is good in an approaching lows and tropical waves – they can’t get it together… usually. Fast also means you have less time and have to start considering options earlier. The forecast was insistent that it was going to stay south, as far south as Grenada, and that whatever developed would be ours in the southern Windward Islands. And it was forecast to develop and intensify.

I predicted that it would pass north of us and I would bet on it. Most hurricanes do pass north of us… well, Hurricane Ivan didn’t… nor Emily eleven months after Ivan. But most of them do. That’s a pretty safe bet this early in the game. And tropical storm Lisa, which had started near where this wave was, had just gone northwest a thousand miles and fizzled down to a tropical depression in mid-ocean.

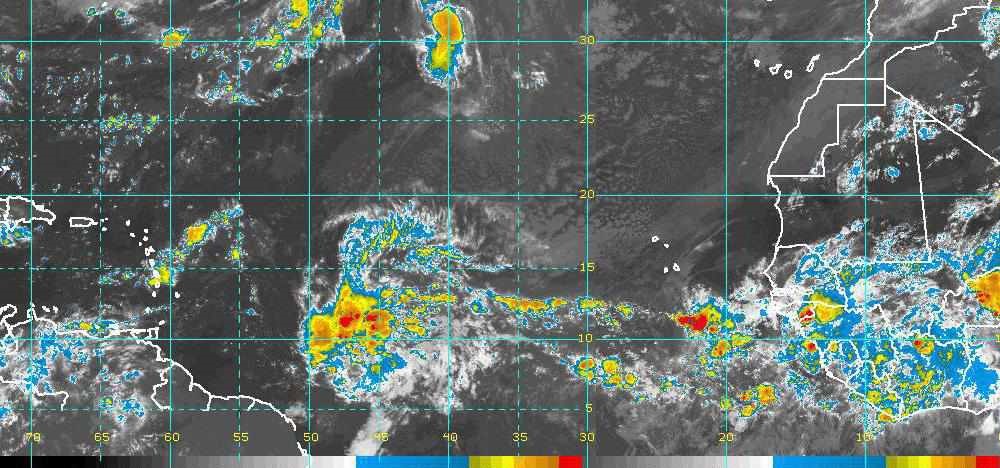

On 28 September, Monday, the low and its wave were a huge mass of weather wider than the Lesser Antilles. It was ten degrees (600 miles) east of us with the low-pressure center still south of our latitude. It wasn’t even a depression or a storm, no cyclonic rotation. But the low now earned a designation – 97L. Both the actual track and the forecast stood on. It was going to hit us dead center here in the southern Windwards. While I was still willing to bet that it would eventually turn north, it was threatening enough for us to prepare in any event. The forecast said that 97L would slow, begin to organize and would intensify into a full hurricane as it approached and crossed the Lesser Antilles into the Caribbean Sea. And it was a very large blob of convective weather – some part of it would likely be ours.

So I went into the mangroves, where there is no wi-fi – no more weather graphics for a while. But once I decide to put in for shelter, forecasts become secondary. I’ll be setting up for a hit that is one step harder than the forecast calls for.

Paul, TMM, and several others had small fleets they were watching for absentee owners. Our early warning is when they and the Sea Rose, Carriacou’s floating metal shop, start moving into the mangroves. Then I check the weather again and make my decision… taking into account the least favorable forecast. This time I was also keeping an eye on an absentee friend’s boat, which was also watched by Paul. When Paul started moving his fleet in, I moved her boat in. So that I could watch them both, I followed with my own yacht to claim the space beside her.

Cassiopeia I and Ambia are small boats. Cassi is a Tartan 33, only nine feet longer than Ambia. Both have operating propulsion. So I single-handed each of them in, chose their spot, anchored them just off, and started running lines into the mangroves. I had moved in too early, at least a day too early, so I left both boats standing off moored between anchor and lines ashore. I am what one Compass editor calls a septuagenarian, so I worked slowly and carefully. It was a hot, breezeless day, sweaty work. That was followed by a hot, breezeless night screened in from the bugs. I have a small fan over the head of my berth so I can sleep in a breeze, not a pool of sweat. I don’t use it often here in the trade wind, but it is worth having when I do.

The next day, Tuesday, the day I should have moved in, there was a nice little breeze. The forecast hadn’t changed except that the center was now expected to pass a hundred miles north of us late Wednesday… the center of a blob of weather that was still six hundred miles across. I reckoned tropical storm conditions at worst, probably less – except in squalls. The forecast now put us in the “navigable semicircle” in which a system’s forward movement is subtracted from the cyclone’s wind speed – in the “dangerous semicircle” the storm’s movement is added to the wind. But either semicircle can be dangerous.

So that I wouldn’t have two boats to deal with if I proved wrong, I went ahead and snugged Cassi into the mangroves, picking a spot were the limbs would separate either side of her forestay. I pulled her bow firmly into the roots with ropes spread to either side led to the cockpit winches, then snugged up the bow lines. Cassi would be fine that way for storm conditions. Check my “Shelter From the Storm” in Compass’s archive for threats of full hurricane or worse.

For now, I left Ambia hanging between her anchor and the trees, out where the living is better, more breeze and fewer bugs. I could pull her in on short notice if necessary. I was still expecting conditions that I could have survived anchored in the bay. Plus, we were now landlocked from any swell. The cyclonic wind would be into the open side of the bay we’d just vacated, blowing waves onto a lee shore.

With most of the work already done, Tuesday was largely a lay day. I did a dinghy paddle around to see who was here and how they were set up – they looked fairly secure for what we were expecting. I had several visits from other yachts that had come in. Also, Georg, who brought in some boats that Arawak Divers was watching, was making the rounds in one of the plastic beach kayaks that Arawak rents. I commented that he had the perfect boat for running lines into the mangroves, low, narrow and pointed so you can take a line as far as possible into the mangrove roots before having to climb into the trees. He joked that I shouldn’t tell, it was a secret. But useful secrets should be shared. For instance, Sally, Paul’s wife, packed a big bottle of drinking water for each of Paul’s crew. Don’t dehydrate and avoid heat exhaustion. You need to last long enough to set up properly and then to deal with the weather itself… if any.

Tuesday night there was a breeze and it rained. Ambia was closed up and I was snug-as-a-bug-in-a-rug with my frugal little fan blowing on me. Being rested when it begins is a good idea. Tomorrow night could conceivably be (though I doubted it) an all-nighter.

#

A tropical wave and low pressure south of the Cape Verde Islands on the Africa side of the North Atlantic Ocean, 2400 miles upwind of us was speeding across the ocean, but forecast to slow and strengthen just as it hit us in the southern Windward Islands. And yes, it was forecast to stay this far south. Our hit probably wouldn’t be too serious… on the other hand…. So most of the fleet moved into the local hurricane hole. I thought that the precaution was probably unnecessary, but I moved in too – I set up more often than I get hit. And so far, I haven’t been hit when I wasn’t set up. So here we are again, tied in and waiting for the massive low pressure system designated 97L that will soon become tropical storm then hurricane then major hurricane Matthew.

#

Wednesday, 30 September 2016 was “storm” day for us, forecast to start late afternoon and continue through the night. There’s a lot of popular lore about how storms seem to always strike at night. And there is much anecdotal evidence as many storms do strike at night. Still, one wonders where the storms are during the day.

About a hundred boats had moved into the mangroves for protection. While that’s a crowd in this particular hurricane hole, I’ve seen twice as many, lots of them inbound, fleeing from the north. But yachts tend not to flee towards the storm’s forecast track, which was where we were. So it was a fairly local crowd. Perhaps being on the storm’s forecast track is a safety factor – I often regard the other boats as a bigger threat than the weather itself.

Wednesday’s weather was cloudy and breezy with occasional small squalls. I was restless, so sailed my little dinghy out through the mangroves and across the bay to have lunch and maybe see a current satellite picture. Once out of the mangroves it was pretty lively sailing. About halfway across the bay the sky darkened and I got the sailing rig down just in time to avoid a knockdown by the first gust of a substantial rainstorm. The squall ended as I finally made shore by paddle power and pulled up dripping wet. The wind persisted, maybe 15 to 25 knots, and I paddled hone across the bay close under the land then sailed bare pole down the mangrove creek to my spot.

It blew an intermittent gale that night. And my how it rained. The water in my dinghy was deeper than I’d seen in years. And during the night and into the morning surf could be heard crashing onto the cobble shores of the bay just the other side of the mangroves. A report from a big boat that had stayed in the bay said that there had been a bit of pitching in a short swell. That report from an English sailor, which, compared to another account, was a bit of an understatement.

Most of us stayed in the mangroves Thursday as well, expecting more swell in the bay.

My next satellite look at the storm was Friday when I brought the two yachts out of the mangroves. By Saturday’s satellite, 97L had become category five Hurricane Matthew dominating the central Caribbean, still a five hundred mile wide blob of weather but now with cyclonic circulation, two huge areas of intense convection, and an eye. And, in marked contrast with the twenty-five knot speed of 97L, Matthew was now moving at four knots, very slowly.

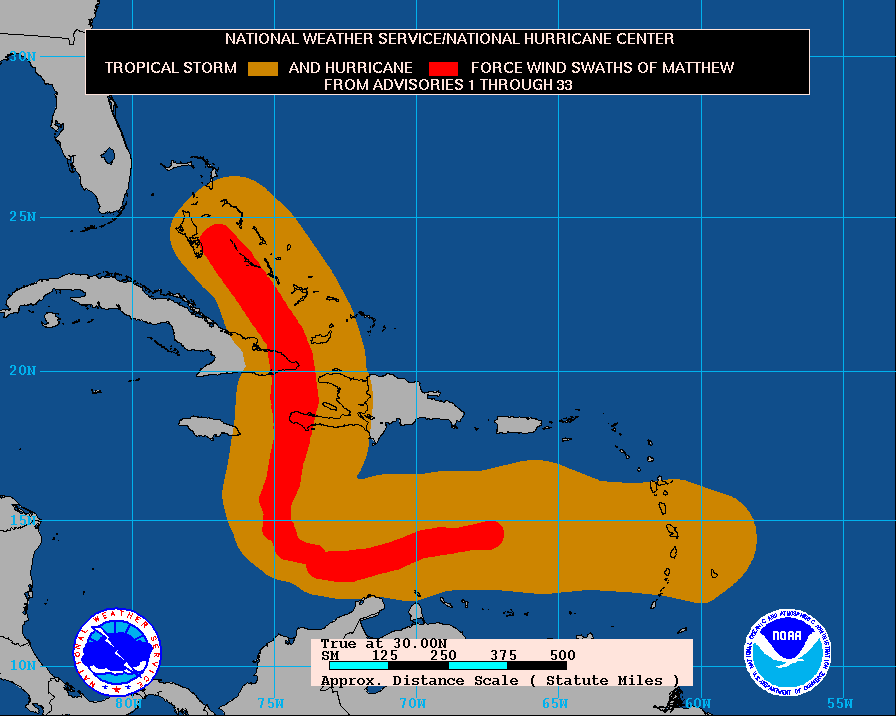

For us, 97L had passed. For others, major hurricane Matthew was approaching. Over several days the storm made a sharp turn to the north, narrowly missed Jamaica, hit the southwest peninsula of Haiti full strength, went through the Windward Passage and over the east end of Cuba, and did a northwesterly turn to pass up the southwest Bahamas over the Tongue of the Ocean. After that, Matthew hit Florida and points north.

The path of Matthew’s storm force winds was 250 miles wide. The path of hurricane force winds was less than a hundred miles across. Matthew’s force four and five winds covered a small fraction of that. My story is about dealing with a rather ordinary degree of threat, a hazard that can be readily weathered if you prepare – but might get you if you don’t. About one in four storms that I prepare for could have got me if I hadn’t prepared. I didn’t think we’d get hit this time, but I took it seriously anyway. Doing all the work to move in and secure, then undoing it all, untying everything, moving back out, and stowing everything to be ready for the next threat, was practice. I was glad I’d done it, even though it had not been strictly necessary… still, it had saved me the hardship and stress of a buckaroo night at anchor in a short swell. The change of pace and extra work felt good despite interrupting about a week of my regular routine. And I was reminded how spoiled we are in the southeastern Caribbean – other than occasional killer storms, things are pretty soft here. Still, I know sensible, seaworthy sailors aboard very capable yachts who make it a point not to be in the hurricane belt during hurricane season.

As it turned out, that was not the end of our dealings with Matthew. Several days later the west swell that the southern half of the storm had built up while Matthew was category five in the central Caribbean began to arrive in the Windward Islands. The swell had traveled hundreds of miles against a moderate easterly wind, so it was long and low, not particularly uncomfortable out on the bay. But it was breaking heavily on the shore, washing sand over the seawall, and tearing up the dinghy docks.

Then 97L / TD #14 / Hurricane Matthew really was gone (for us), the swell Matthew had kicked back from the central Caribbean was finally gone, and the dinghy dock was gone. The sand had been shoveled and swept out of the Gallery Café and I was having breakfast when Ellie, who had also moved her yacht into the mangroves, came in and said, “That was a good exercise.” That says it real well. On this particular island we hadn’t had a scare that made us run for cover and go through all the bother of setting up for three hurricane seasons. We needed the practice. If our next storm threat is soon, we’ll be ready.

Most of the people who experienced Matthew to some degree didn’t have much problem. To those who were nearer the eye when Matthew passed it is an entirely different story – well over a thousand died.

Caribbean Compass June 2017