My day and night aboard Jane got me rolling. I got on the bus, rode straight back to Colorado, began liquidating my life ashore, got a passport, and began reading what I could find on the lifestyle. Nine months later I hit the road with sufficient money to buy and fit out a small yacht.

I found Ambia at Tarpon Springs, Florida, converted her from a daysailer to a live-aboard cruiser, and set myself to learning the lifestyle. By the end of my first year aboard I had done two cruises in the Florida Keys, a brief visit to the Bahamas, and had ventured up the East Coast via Canaveral, Beaufort, NC, around Cape Hatteras to the Chesapeake Bay, and up to Annapolis. Then we turned southbound well in advance of winter and were working our way towards Florida when Hurricane Gloria came our way.

Gloria was a life and death situation. I am pleased with the decisions I made and the actions I took, especially given the outcome – it could well have been the end. But it is clear that, even a year on, I wasn’t much of a sailor.

Winds and seas were light off Hatteras Island the morning of Wednesday, September 25, 1985. Radio station WWV’s condensed rundown of Atlantic weather, the synopsis squeezed between the time signals of minutes eight, nine, and ten each hour, had put Gloria 900 miles southeast yesterday afternoon. Her winds were a hundred, her track WNW at fifteen. She still seemed a fair piece off, headed for the Bahamas or Florida. [I was still a novice with regard to tropical weather.]

We lay quietly at anchor, outside of the Outer Banks of North Carolina in thirty-six feet of water, three-quarters of a mile offshore, several miles from Hatteras Inlet, in a big danger area that says not to anchor because of mines on the bottom. I figured we deserved enough luck not to drop the hook smack on a live one, and if we picked up a cable… well, we’ve dealt with that one before. I lay below in the comfort of the blanket reserved for times when Ambia and I are dry, which hadn’t been lately. There had been a night of rain, a night of tropical storm Henri and a day of beating our way out of the Gulf Stream against northwest winds in leftover seas.

Ambia had been magnificent, but her sails needed some looking after. The repairs to the main following tropical storm Henri seemed sufficient, but a repair made on the working jib prior to departure from the Chesapeake was beginning to strain. The helm creaked some, a problem yet to be dealt with in Beaufort. One of the two batteries was exhausted due to a lack of sun for the solar panels and particularly high usage of lights and loran. The loran’s low power alarm, while on anchor watch, had awakened me earlier.

Our route had been across the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay from Hampton, then outside and down the Outer Banks. The passage had been made within sight of land to avoid the current farther offshore that had helped us northward two months earlier. Three days out we had encountered tropical storm Henri twenty miles northeast of Cape Hatteras and had run offshore. The fifth day out, the 24th, we had finally rounded Diamond Shoals off Cape Hatteras and come in the evening to our present location. The plan now was to go inside, go ashore, pedal the bike out to the lighthouse to snap its picture, and spend another quiet night at anchor. Then across Pamlico Sound to Oriental to visit Bob of Vacilando, who I had met on the Chesapeake.

I made a leisurely start with all the amenities of a quiet anchorage figuring to negotiate the inlet at low tide slack water around noon. I checked for fringe reception on Weather One and Two. There was none. NOAA uses Weather Three at Hatteras, the one our old VHF doesn’t have… yet. That was okay, I’d browse through the Coast Guard’s wealth of weather information while ashore.

We weighed anchor a couple of hours ahead of the changing tide and drifted toward the inlet under working jib in a rising breeze. We arrived at the entrance an hour later in a stiffening wind, the eye of which was roughly aligned with the inlet. I tried first with working jib and outboard, then using the outboard alone, at as much power as I risk unless it’s that or the rocks. Evin, our six horsepower docking motor, couldn’t make steerage into the wind and waves, a good sign that motoring in wasn’t going to work. I raised a reefed main to see if that would help. Miss Hatteras stopped on her way in to see if I wanted her to stand by. I declined and hove to for a bit to think it over. A decrease in wind or a change in wind direction would let us in. In the present wind, Beaufort was a day away, outside around Cape Lookout. I called the Coast Guard to see what was expected. What I got was the latest on Gloria including the unexpected news that we were under a hurricane warning. Gloria had almost halved her distance, intensified, and was heading our way. He went for the local forecast, but came back with, “I’m going to have to put you on hold, one just capsized in the inlet.”

I wasn’t so sure I wanted to try Hatteras Inlet now. Nor did I relish trying to outrun Gloria to Beaufort, though my guess was that we could pull it off if the wind – and sails – held. Ambia is a Bristol 24, an ocean capable boat; she was selected and outfitted for offshore work. Our prearranged weather strategy is to run offshore. The obvious course was to run offshore in the Gulf Stream. With the current, we could conservatively count on making six knots over the ground, more for the first day or so. And we would be running from Gloria… granted, on her more dangerous side. What if she followed? We would be “it.” And she seemed strong, even for a hurricane. Beaufort. Maybe we could get in at Ocracoke along the way. A full main seemed plenty of sail for the broad reach to Ocracoke.

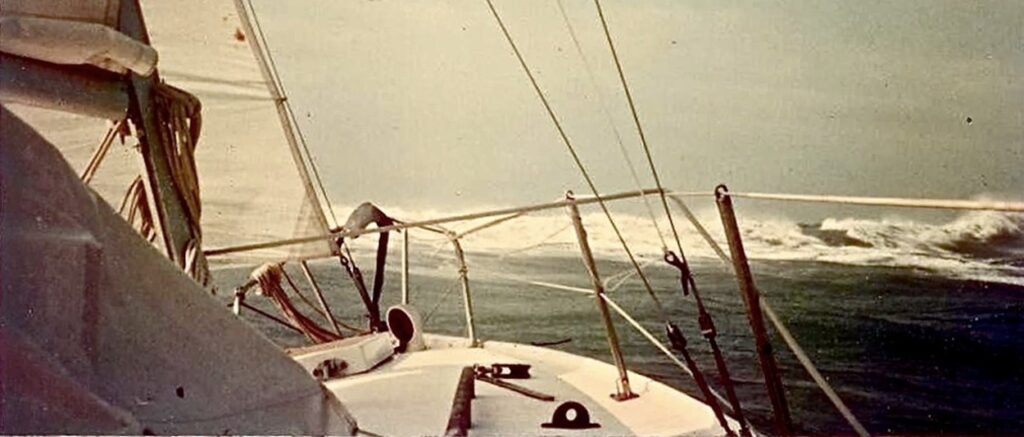

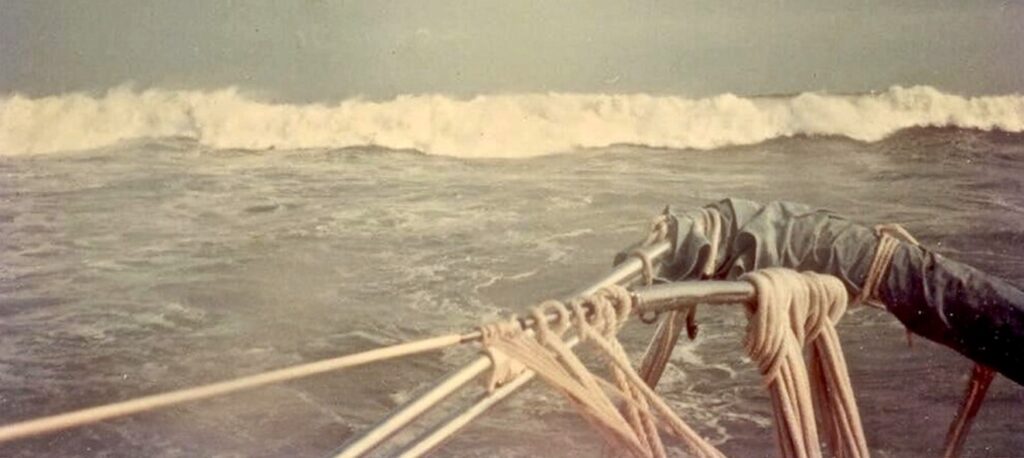

The waters off Ocracoke Inlet were churning in large areas of surf that extended from shore nearly to the sea buoy when we arrived and were visible long before the buoy. Some of the outer buoys were occasionally visible on the crests of waves. From the buoys I could see and what I guessed to be the lay of the channel, the breakers seemed to be crossing the channel. Could that be? Was that the channel? Did the channel take a turn into the wind anywhere along the way? The inlet channel is not charted due to frequent changes, but the charted depths indicated a straight shot of almost two miles, shoal on either side. I reefed the main, raised the working jib, started Evin, and squared her with the channel. We were close hauled. The wind would be favorable should we have to turn around, but what about the incoming surf? There was no way in hell that I wanted to try this.

The words of a Sweet Haven sailor echoed in my mind: “Man, you don’t want to be out there in one of those.”

With Evin at about a third power, just short of screaming when cavitating, we started in. I had no clear idea what we would do if we made it. Teaches Hole Channel would lie near the eye of the wind. Perhaps we could short tack its three mile length, maybe we would have to anchor and call for help. Soon wave after wave of surf was racing in on either side of us, breaking continuously over the shoals, sometimes across the channel. I kept her hard to windward, several places windward of the channel – if she grounded there, she would come off. Grounding on the lee side of the channel would cost me the boat, maybe more. Several times a series of breakers overtook us on the starboard quarter. Each time I was relieved at how well she took them. She held her course far better than her usual in following seas. In the Chesapeake, we had surfed down several waves in seas smaller than this. But she did not surf. The breakers overtook us at about twice our speed, lifted her stern up through the breaking crest, and passed beneath us. None broke aboard, although there was considerable spray.

Recollection of anxious situations is often cloudy, and the workload was such that I did not record times and observations in the deck log during the passage in through the inlet. My remembered impressions are that the wind was in the twenty-knot range, from the north, and that the height of the breakers was typically six to eight feet. Boat speed surged between about three and six knots. The tiller still had two inches of play from our night with Henri, but she seemed well balanced under the reefed main and working jib and reasonably steady on her heading as the seas rolled by.

Then we had made it. The wind still howled and the surf still crashed ashore behind us. But now we were in two to three foot seas inside the cut. I tacked back towards the channel that lies along the inner shore of the island, watching the surf and blowing grass, near disbelief at what we had gotten away with. Then we tacked, and tacked, and tacked…. Almost always I took her wide of the marked channel reading the unfamiliar waters as best I could. Once I thought we touched bottom while tacking, but softly. The really shallow stuff was plainly evident. Stakes, markers, and lesser murkiness marked other areas. Evinrude helped considerably in keeping our speed up during tacks. Soon I saw that we were doing far better than expected; the tide was coming in hard, pushing us onward. Finally, we reached the mouth of Silver Lake, a sight more beautiful than I can say, its waters nearly flat, its winds light. I had expected a lot of boats here, people hiding from Gloria. There were almost none. Most had already forsaken the shelter we had worked so hard to obtain.

It was decision time again. We could ride it out here, leave this relative haven and cross unfamiliar Pamlico Sound at night in conditions that would surely continue to worsen, or I could secure her as best I could and escape by ferry. I ruled out the latter and agonized over the other two. With the safe solution discarded, I decided on double or nothing. We would run for it. Just over an hour was spent ashore getting gasoline and high sugar snacks to keep Evin and me buzzing all night and making an important phone call to one who waits. The first car along offered a ride to the gas station, the same returning. That’s how folks are in times like this. Peggy was one, I’m afraid I didn’t catch the other’s name. Then I boiled a thermos of hot water and suited up all the way – full foul weather gear and safety harness. I had had the top of my foul weather gear and the safety harness on for the surf event coming in and was still dry, for which I was grateful.

The deck log was soaked, so our navigation log was kept on the bulkhead beside the compass. At 18:35 I slipped the lines. Night would soon be upon us. There would be a gibbous moon on the overcast, but it was going to be dark down here. I wanted to clear Nine Foot Channel, for sure, and Royal Shoal, if possible, in some light. I also wanted to cut the first corner out of the harbor as tight as possible to minimize our exposure to Big Foot Channel, which lay twenty-five degrees closer to the wind than the rest of our route… one of those, “if we can just get that far, we can manage the rest” things. We sailed as before under reefed main and working jib with Evin at one-third power. The wind felt stronger, possibly an illusion following our quiet hour on Silver Lake. Arrogance or numbness or something prompted me to head due west for the channel, across what appeared on the chart to be a small point of shoal. Someone at Ocracoke had commented on how high the water was already, and it was still rising. To the lee of the hazard was the good water of the channel. It seemed worth the risk. And we were getting away with it. Then I slackened the mainsail some, for we were heeled quiet a bit. Thud. Recognition, we'd hit the bottom. Thud. Harden up. Thud. She lay back over. The appearance of the water was the same in all directions. Keeping her heeled, she cleared the bottom the rest of the way. We made the lee corner of Nine Foot Channel without tacking.

I bore off a bit when we made the windward side of Nine Foot and freed her up some more passing Royal Shoal in the gathering darkness. With Evin’s help, the knot-meter ranged from five to six. The seas seemed surprisingly moderate, two to four feet, occasionally six, not what I had understood to be normal for Pamlico Sound under a strong wind. And, while something about the sea state wouldn’t let the sheet-to-tiller steering work, conditions felt pretty civil, all things considered. I reminded myself that a night of sailing in unfamiliar waters and of working our way as far as I dared up Bay River still lay ahead of us, not to mention the main event herself.

“Fatigue is the enemy,” John of the 1877 coasting schooner Governor Stone, once warned me. Judgment begins to go. Not that I felt fatigued. In fact, I was in my second wind and beginning to have a marvelous time. I kicked back, relatively speaking and settled in for a long night at the helm, pointed squarely between Lower Middle Light and Brant Island Shoals Light towards the shelter of Bay River. Now, some of you can tell me, that’s the way to Pamlico River. Bay River lies south of Brant Island Shoals. And much of Brant Island Shoals, which extends halfway across Pamlico Sound towards Ocracoke, is too shallow for even our modest draft. The Pamlico River would have been okay, but would have involved twice the distance to the kind of shelter I felt up to navigating in strange waters at night. I was due north – upwind – of Brant Island Shoals Light when I figured it out. Such errors can blow a victory that seems assured. In this case it just cost us half an hour and exposed the creaking helm to unnecessary stress from following seas.

The moon and stars began to poke through and the wind abated a few knots. It was becoming a magic, though still lively, night for sailing. Then we were across, approaching Bay Point Light, orienting to the lights – trying to. They weren’t right. I hove to and went over it several more times. They still weren’t right. There was an extra red light to the south, and to the west, where there should have been a four second green, I saw a four second red. (Marker “2” in Maw Point Shoal to the south was now lighted and, for some reason, Bay River marker “4” was visible while “3”, at half the distance, was not.) I evoked the sorcery of loran to verify our position then proceeded up the river. We anchored at 02:18 and I slept until dawn.

Gloria’s morning position was 350 miles south. She was as strong as ever and her apparent target was still Morehead City, thirty miles south of our present position. By late morning we had worked our way a mile and a half up Vandemere Creek, off Bay River, past three other sailboats anchored at three to five hundred yard intervals. Like them, we anchored mid stream, in eight feet of water. The heavier of the two storm anchors went downstream against the expected rise of water. I would worry about the receding water if we got that far, though survival now seemed a matter of properly completing our preparations. With the rodes of opposing anchors taut and their turns on the winch groaning, I lashed the mainsail and stowed the jib, letting the motion of the boat work the anchors deeper. After winching again, I transferred the stern line forward and let out a couple of boat lengths for her to swing on. Then I set about the little things, furling and lashing the ensign to its staff, lowering the owner’s signal, extra lashing on the rolled up bimini and such. There wasn’t much, for we were still secure for sea.

Three working boats came up the creek for shelter, a little guy and two large trawlers. The little guy tied off to several half beached wrecks of similar size, a pile he later joined. One of the trawlers anchored mid-creek a couple of hundred yards upstream. The third, the largest of the three, anchored between us and shore, four or five boatlengths off, outrigger booms down. Then they all rowed ashore and drove off. It seems we were near a convenient road. I wasn’t too happy about all this, but I’m not much good at telling people they aren’t allowed to anchor where they are allowed to anchor. It would be okay if nobody dragged. I figured we wouldn’t drag for the same reason I didn’t fancy pulling the deeply set anchors and moving. Logic prevailed, however, and I decided I’d better do the move while things were still calm.

The second anchorage was better anyway. I got out the lead line and scouted out a place closer to shore, just around a grassy little point from the working boat fleet. We were off a small house either vacant or boarded for Gloria, with a small dock for the dinghy or whatever, a perfect tide gauge. The dock had a foot of freeboard.

I went below and made some bread. Gloria’s turn. She was 200 miles away, still 130 mph strong, her central pressure 27.82”.

The other sailboats were also unattended. I was the only one staying aboard. They had gone to look after their homes. I was aboard my home. There is little question that it is safer ashore. Or that the boat is safer with someone aboard.

While I had never experienced a hurricane, I am not unfamiliar with high wind. What I did before the system burnt me out was teach light airplane flying in Boulder, Colorado, where chinook winds might top a hundred miles an hour during winter. During such storms, my job was to try to keep the airplanes from being destroyed. There are some important differences: The hazards to the airplanes consist of wind and blowing debris. A boat must also deal with the rising water and the currents accompanying the storm tide, and with flotsam. Furthermore, the wind at a mile above sea level has significantly less force than the same velocity of wind at sea level since air density decreases with increased altitude. A direct hit from Gloria, which still seemed likely, could expose us to more wind force than I had ever experienced. I tried to imagine such a wind and how Ambia would react to it. I ran the spinnaker halyard to the bow to backup the forestay and sweated it down, along with a halyard I have rigged at the spreaders. I checked and rechecked everything and tried to think of anything left undone. A world-class sailor I had met in Annapolis, Cass, now of the trimaran Tortuga Too, had weathered a hurricane stronger even than Gloria. He had told of difficulty in crawling to the pitching foredeck against such wind. I tied the jib sheets to the base of the bow pulpit, tracked them aft along the sidedeck, winched and cleated them, making a handrail at deck level. Susan, formerly of the 70-foot brigantine Varua, who I had met in Colorado immediately prior to my departure for the cruising lifestyle, had cautioned me about inadequate ground tackle and excessive freeboard. Ambia’s relatively low freeboard had been part of her attraction. As for her ground tackle, both of her working anchors – a Bruce and a High Tensile Danforth – are storm rated for her size. For this occasion, I would just as soon have had the next larger size. What I didn’t think to do was to ready Ambia’s former working anchor, a twelve pound Danforth kept strictly as a spare.

I tried to get some sleep, for it would surely be a long night. After a while I gave up.

A bunch of folks have got their own tales of the night Gloria hit, a lot of them – happily for me – more interesting than ours. By dark the winds had picked up to the twenty to thirty knot range in puffs, pretty much down the creek, out of the north. By midnight, I figured it to be in the thirty to forty knot range. Ambia began to tack hard, heeling ten to fifteen degrees when she hit the end of the slack on her downwind anchor. At 01:12, civil defense sirens sounded ashore. Shortly after, I noted that Ambia was heeling up to thirty degrees, in a lurch, when she changed tacks. Shortening up the lee anchor helped some. It was a strange motion. Things that had never before been a stowage problem were pitched from shelves. At 01:59 I logged “extreme gust.” At 02:22, “wind still increasing.” Blowing sheets of rain and spray torn from wave tops reduced visibility to nil in gusts. 02:48, “gusts more frequent.” At 02:58, “gusts almost continuous.” Our barometer was in the shop for its second warranty repair, so I can’t say what the pressure did. The tide rose no more than a foot where we were. Presumably the wind was keeping it out.

At 03:06, “seems to be slacking.” The eye of Gloria had passed over Hatteras an hour ago, still packing 130 mph winds, her central pressure nominally up to 27.98”. Her center had passed 50 miles east of us. My estimate of the maximum gusts we had experienced is on the order of fifty to sixty knots.

Fifteen minutes later the moon was briefly visible, there were occasional lulls into the ten- to fifteen-knot range. In another twenty minutes the rain had stopped. The winds became westerly, ten to fifteen gusting to twenty. Shortly after four AM I stood laughing on deck. “It’s over!” I shouted at the dying wind, “Let the party begin!”

“Or was that the party?” I answer.

At 04:09 I went below and turned on NOAA for an update. They were not transmitting, a token reminder that not all would have come through unscathed. The trawler that had caused us to move had dragged a quarter mile past us during the night and grounded. And others had yet to meet Gloria. Bob, while watching Vacilando, had helped fight a fire that consumed Oriental’s grocery store during the storm. Its ruins were still smoldering when we docked. The south of Cedar Creek, just off the Waterway south of the Neuse River, a recommended hurricane hole, looked devastated, with trees down all around the shoreline, twisted docks, and a trawler so far ashore that she looked like an exhibit. The wind must have funneled straight down Adams Creek into the anchorage. Occasional buoys and channel markers were missing along the way. All in all, though, most of us seem to have come out of it pretty well.

What if I had run offshore? I plotted it out. With moderately hard sailing and no equipment failures I would have been a hundred and fifty miles from her eye on her stronger side, two hundred miles off the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. We would have celebrated Gloria’s passing many hours later, expecting another day or so of her seas. Then we would have slogged our way back out of the Gulf Stream again and, in a week or so, we would round Cape Hatteras once more. Still, it would have worked… unless she had turned.

I recall a day last spring, aboard the catboat Harbinger somewhere in the Florida Keys, sipping a rum and coke and watching another day in paradise end. Captain Schlake, who hails from Sweethaven as much as anywhere, prepares one of his famous seafood dishes while telling of the one that nailed Islamorada in… was it ‘35? “Man, you don’t want to be out in one of those,” he says.

#

In Beaufort, I broke out my copy of Waves, Wind and Weather (Bowditch), and reread the chapter on surf. What I experienced at Ocracoke Inlet was likely spilling breakers as opposed to plunging breakers. As for surf crossing the channel, I am too new to the sea to know how common that is. There was, in fact, a growing disbelief within me during the week that lapsed before I saw the photos. (They were shot with a somewhat wide-angle lens by a Hanimex Amphibian.) That the inlet is entered over a bar explains the first set of breakers. That the wind and tide were both strong and in opposition was surely a factor.

That the tide was in our favor, plus a pretty fair boat speed, likely explains why she took the surf so well, not to mention being responsible for our having made Ocracoke Harbor with daylight and energy remaining. Otherwise, it might have been a different story…. An old cowboy friend in Colorado likes to tell me, “Jimmy, I’d rather be lucky than smart any day.” Right Rex

Carolina Cruising, Dec/Jan ’86.

One Response

There is a quiet, deliberate beauty in the phrasing. Each sentence has weight and flow, inviting observation, pause, and mindful engagement with its layered meaning.