Bequia’s western peninsula, from Moon Hole Arch to West End, has a scattering of fanciful stone houses. I once lived there – kind of.

Get comfortable, this is a long one.

I met Jean Poisson at the Whaleboner on Bequia around ’96. He invited me to Roundhouse, his Moonhole house.

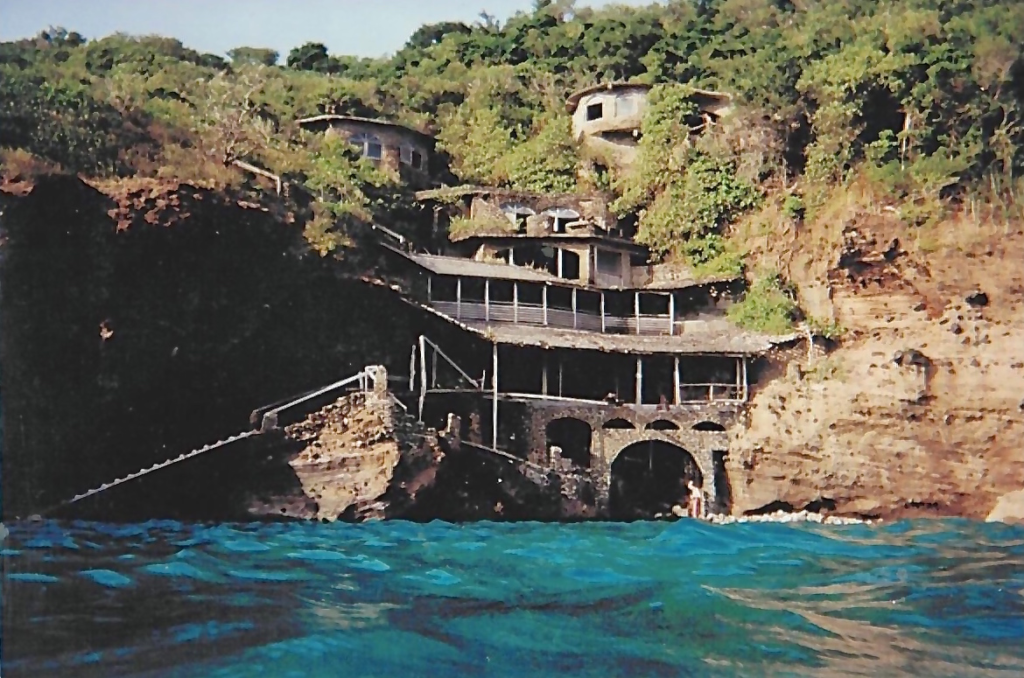

Moonhole is on Bequia’s narrow southwestern peninsula, a volcanic dike extending half a mile from Moon Hole Arch to West End, rocky, much of its shore precipitous, covered with bush and trees. The land is left natural except for a scattering of large rock and concrete houses suggestive of abandoned castles – except for their huge open windows and doorways – and never a straight line.

Jean Poisson’s Roundhouse was outside of the palm-frond entrance into Moonhole – Roundhouse was an autonomous Moonhole house, separate. Jean was a twenty-year friend of the Moonhole family, the King of whom was Tom Johnston. All building and rebuilding within Moonhole was entirely King Tom’s prerogative. But Jean’s house was beyond Moonhole’s jurisdiction, outside of the gate. Jean could build and rebuild as he liked – which he did. Originally, Roundhouse might have been Tom’s smallest house. It was one story high when Jean bought it. Jean doubled its size by adding an open second story, two-thirds covered by an observation deck/rain catchment. Roundhouse was Jean’s project. As amazing as it was, and continued to become, it would never be finished.

Jean took me out to Roundhouse in the Blue T’ing, his three-wheel Cushman scooter with a two-person cab and a small cargo box, such as meter maids and mailmen used to use. We chugged up the long hill out of Port Elizabeth, down through Friendship Bay and La Pompe, around the point and through Paget Farm, then along an uninhabited sandy lane between palm trees lining the beach and dense island bush. He parked Blue T’ing at the end of the road, outside of Moonhole’s palm frond gate. Then we climbed the sixty-four steps winding up through the trees to Roundhouse. At a curve halfway up the steps where the house first came into view through the trees hung the bell, a bronze porthole as the gong and a deck cleat as the hammer. All Moonhole houses have a bell to announce arrivals.

The steps continued up past the sub-level of the house, which was a huge cistern with a half-open alcove in its face furnished with a bed, beside an outdoor shower and a loo with a view. The stairs became a path around the main level of the house, between its rough rock wall, hung with Jean’s antique British Seagull outboard and a large piece of Tom’s whalebone art, and a handrail at the edge of a sixty-five-foot precipice to the sea. Beyond the open-arch entrance and a large open window, the path ends in stairs to the upper level – mounted on a large driftwood tree Jean found on the beach. Jean later found another such tree on which to mount the steps (not stairs) up to the third level, the rain catchment and observation deck.

The house was massively built and round. Tom Johnston had decided on the theme “Roundhouse” based on the name of the man who had commissioned it, a Mr. Trane. The axis of the house was a rock column at least ten feet in diameter rising through the main and second levels to the partial third level, which covered two-thirds of the second level. The second level had stone pillars only, not walls, with open mesh screens on the weather side (east) to slow the tradewind and the infrequent rains. Jean was still building and the open second story eventually had many planters full of various flora, and a camping tent on a platform, which was a bedroom. There were lots of places to hang out – our favorite being two hanging chairs overlooking the view, slung beneath the structures that Jean dubbed “the Pitons” – which were the only part of the house that could be seen from the road coming in. The view of the Grenadine Islands to the south was picture postcard stuff.

In the left of our view lay Bequia’s small airport, running beside the shore on its own rip-rap island. Base leg for landing was sometimes over the house, final approach was a bit south of us – long final. Most arrivals flew tighter patterns. Jean had been a pilot and had owned a two-seat airplane of a kind I taught people to fly. We sat in the hanging chairs talking about everything else until an occasional airplane cane in, during which we would critique the pilot’s performance. Jean judged less critically than I.

The main level of Roundhouse had a living room with two huge open windows with a view through the tops of the trees, a kitchen with a large, open window onto the north shore, and a dining area and large bedroom. The two entrances into the house were archways with no doors. Sometimes birds would shortcut through the house. The distinction between inside and outside in Moonhole houses is tenuous and circumstantial. For instance, one retreated toward the center of the house in a blowing rain and migrated during the day to stay in the shade. The critters went freely where they would but generally found life to be better outside of the house. Any ant trail within the house would lead to food that they were carrying back to their colony, food that had been dropped or left out, a large grasshopper that had died in the house or a lizard that Miss Kitty had eaten only the choice portions of. Miss Kitty was well fed – she only hunted for sport. Miss Kitty’s bowl was kept on a plate with enough water to form a moat against the ants. Lizards were everywhere, inside and out.

The ants were a vigilant cleaning crew. But Jean also had a maid, Hyacinth, who came several times a week. Jean claimed that she moved things around on the shelves to make it look like she’d cleaned. Hyacinth was a pleasant person and lasted a long time.

Hyacinth once commented on how much cooler Roundhouse was than Paget Farm, where she lived. She wondered if all of the trees had anything to do with it. At Roundhouse, the trees had to do with everything. At the foot of the sixty-four steps up to Roundhouse was a flamboyant tree that covered the lower steps with a royal scarlet carpet of fallen flowers at the beginning of wet season. The trees through which the shaded path climbed obscured the house from view until coming to the bell. Most of the trees were adorned with epiphytes, plants that grow on trees, often many to a tree. Epiphytes are mini eco systems of their own, home to little critters, with water caught by their leaves collecting at their base. There were gum trees with thick limbs sprawling every which way in abstract shapes. Flowers and hummingbirds were everywhere in season. Here and there were bird nests.

Jean trimmed the tops of the trees to the south for a view of the Grenadine Islands – all the way to Grenada on days that African dust didn’t dull the air.

At the base of the house was a huge and formidable century plant, big and grey, with thick leaves two or three meters long and edged with sharp thorns, their ends terminating in a dagger-size spikes. When its “century” ended, near the end of my Moonhole years, it extended a tall stalk to the upper level of the house, spewed its progeny to the wind, and died.

Most alluring of the trees was a frangipani ten or fifteen meters upwind of the house. It was among the fullest, most colorful and most fragrant frangipani trees that I have ever seen. When Jean called during one of my early stays at Roundhouse I reported in anguish that a huge number of big, colorful caterpillars were destroying his beautiful frangipani. He explained the symbiotic relationship. The caterpillars eat every single leaf from the tree with remarkable speed. Then they are gone. Then the frangipani comes back better than ever – Roundhouse’s frangipani was a particularly beautiful example. Jean’s neighbor, out of sight beyond the trees, did everything he could to get rid of the caterpillars. His frangipanis were scraggly.

Over the years Jean filled the place with potted plants, many of them cactus. Jean was the only man I knew who grew cactus in his bedroom.

Jean and I became close friends. I visited often when my yacht was at Bequia. Sometimes I brought friends or people I’d met in the harbor. Jean and I liked the same kinds of people and he loved showing off Roundhouse. Everybody was blown away – they’d never seen anything like it.

Early on, Jean went away for three months and asked me to watch the house for him. “Feed the cat,” is how he put it. So, I owe that to Miss Kitty and fed her well.

During my tenure I made visits to Moonhole proper and made friends with old Tom the King, his son, Jim and Jim’s wife, Sheena. They allowed me free run of the original Moonhole buildings, which were built from the sea up through Moon Hole Arch then down to the sea on the other side – seriously fanciful stuff. Jim and Sheena ran Moonhole tours, which were well known and popular. When Wind Jammers and other cruise ships called at Bequia they got eager crowds.

Jim and Sheena’s house, Agnew Hall a.k.a. Stone Manor, at the head of the steps down to “the Hole”, was part of the tour. All Moonhole houses are extraordinary in design, so their house was normal Moonhole in that respect. What made Stone Manor stand out was how it was appointed and furnished and how Jim and Sheena maintained and gardened it. The house was a showpiece of Moonhole life as it had been at its grandest, when Tom’s rich Princeton friends would gather and praise his imaginative architecture and Gladys’ domestic staff and, especially, the gardening. Back in the really royal days of Tom Johnston’s Moonhole kingdom the furniture was built onsite from regional hardwood, cut thick, massive tables and chairs, some throne-like chairs so heavy that it took two men to move them. In Jim and Sheena’s house, the furniture was polished and re-polished to a depth. Rock pools were built under large living room windows, lush with water plants and small fish.

Characteristic of Moonhole houses, the concrete roofs seep water and form stalactites. In Jim and Sheena’s house these were cultivated. In their wonderfully comfortable bedroom suite, a gutter above the bed caught a leak from Hammock Deck and carried it to a corner where it could build a stalagmite on the floor.

Stone Manor’s doorbell was the grandest of them all, large and having a deep, resonant voice.

I had the great pleasure of housesitting Stone Manor several times over the years. I made my bed in an alcove window off the living room overlooking the sea.

In addition to being a Moonhole friend through Jean, it happened that Jim, about my age, had spent twenty years in my hometown, Boulder, Colorado. But it was our attitude towards Moonhole life that we all had in common. Passing through the palm frond entrance, I would tell friends that I was introducing to Moonhole that we were passing from what some call the real world into what I regarded as the real world.

The Hole had been vacated years earlier when a boulder fell from the overhead arch. Then Gladys had died, a devastating blow to Tom. Old Tom, now in his eighties, lived in Hill House, the house that he had built above the Arch. Tom referred to Hill House as the top story of his Castle Glad – for Gladys. Oh the times that Tom and Gladys had and the things that he had done! But now he was at home, mostly playing with camcorders that rich homeowners brought when they visited their houses, and hoping for a chess opponent.

Chess was one of many Moonhole themes. I think every house had a chess set. There was a small workroom in the Hole where Tom made whalebone chess pieces and did other whalebone art.

Tom and I played many games of chess over the years. Neither of us was anything to brag on (although he did), but we were both determined. Tom was about two-games-out-of-three more determined than I was… probably about the right balance when playing against a man who has been King for much of his life.

Tom was a kingly figure, six foot two, strong until recent years, commanding by nature, arrogant to a fault. In the entrance foyer of his house, made large on a wall, was a gift he gave Gladys years back, a set of vows to stop declaring himself the greatest and repenting other related foibles. The gift was made large, bold and arrogant, placed for all to see.

There were well-packed bookshelves all over the place – books were another Moonhole theme.

One wall of the vaulted hall in which we played chess had rows of plaques, awards for Tom’s architecture. But here’s the joke: Tom wasn’t an architect, he was an artist. Each of his houses is a piece of its own, each with unexpected flights of fancy. And when an owner who had just moved into his new house said, ’Tom, the roof leaks,’ Tom reportedly replied, ’Yep.’

While visiting Old Tom, Pamela would quietly keep house and provide for our wants. Moonhole was known for quality domestic service. That was Gladys’ work. The domestics, along with Tom’s prolific building, made Moonhole a really good employer of locals. Many people I met in Paget Farm fondly recalled when they worked there or when, as children, they spent days with their mother who worked there, probably breaking rock aggregate for concrete.

Halfway from Paget Farm to Moonhole is a quarry where, either side of the road, are many piles of broken rock under shades held up by sticks. Several days a week, women gather and sit on top of their pile breaking more rock and gossiping. Their children might be up at the huge cistern at the Adams ruins doing the laundry. Making aggregate was their private enterprise. Nearby were the remains of massive machines once intended to do that work, machines that died in disrepair.

My first stay at Roundhouse was three months. In addition to meeting the family, playing chess and wandering Moonhole, I made two chess sets of my own design, one of different sailing rigs on seashell boats, the other of stick figures made from match sticks – lighting kerosene lanterns and smoking supplied the matches. And I wasn’t just feeding Miss Kitty. There were potted plants all over the house to water.

Mostly it was just peace and quiet. Along with watching plants grow. Before Jean left, he pointed out a leafless stick that looked like a coat rack at the bottom of the house and said, “Watch what that does when wet season starts.” It was a climbing vine, and it was amazing. I made sure that it had water on a continuous basis. It grew nearly a foot per day. I tied it to grow up the side of the house, loosely braiding and twisting it as it grew, until it reached the second story. Then I trained it to border around one of huge open window of the living room.

Watching lizards, iguanas and birds. Watching hummingbirds feed on flowers all over the place, listening to tropical mockingbirds singing on and on. Land birds, sea birds, migrating birds. Listen to the breeze rustle through the trees. The sound of sea waves surging onto the base of the precipice below the north side of the house or waves washing onto Moonhole Beach to the south, according to weather conditions and which part of the house I was in. When a north swell was running, the huge, round boulders at the base of the cliff would wash in and out in waves breaking thunderously sixty-five feet under foot – not a soothing sound for one who lives on an anchored yacht. The north swell was occasional but impressive. Generally, the weather was sunny with a warm tradewind breeze. The sound of a vehicle was a novelty, news, a coming or going at Moonhole – we were at the end of the road.

Then Jean would return from his travels and I would move back aboard my little yacht, Ambia. Sometimes Jean, who had first come to Bequia on his own yacht, would do a little sailing adventure with me. He was my best friend on Bequia.

When Jean was on island there was a Full Moon Party every month at Roundhouse. It was a buffet attended by, say twenty-odd friends, according to who was on island and, during wet season, the weather – parts of the road became quagmire after a heavy rain. One didn’t need an invitation. If Jean was on island, we knew it was on. It started around sunset and the last guests were leaving by midnight. There were places all over the house to hang out. It was pleasant and relaxing. In his book on Moonhole, Charles Brewer referred to the gathering as “midnight madness” – I don’t know what he was talking about.

During my third round at Roundhouse, with Jean off again and me feeding Miss Kitty, I paid Old Tom a routine visit, rang the bell, climbed the steps and found the family gathered around Tom on his dais – Tom, Jim and Sheena. They had been discussing an idea that I was just I time to hear. Would I like a Moonhole house of my own? Ravine House a.k.a. the Stark House, which had been abandoned for over a decade.

I never met George Stark. I knew him only by legend, mostly Jean’s version.

George was the captain of an NFL football team, played end. He was over seven feet tall, solid build, the biggest man Jean had ever met. He was wealthy and a celebrity, so he fit a Moonhole profile, thus was allowed to buy Ravine House. Tom had built the house, which climbs from the sea up a ravine for seven stories to just below the trail known as the Fisherman’s Highway, for someone else… whose wife, on first sight, allegedly said, “No!” Thus, the house had been available when George discovered Tom and his kingdom.

Jean had a lot of respect for George. When in residence, George did a morning jog from Ravine House, through the gate, down the road along the beach to Paget Farm, along the high coastal road climbing up and around Friendship Bay, through the saddle to the Admiralty Bay side of the island and down into Port Elizabeth for breakfast. It’s a nice workout, which took me thirty minutes on a bike. Jean said that George bought breakfast for anyone who joined his jog along the way. Nice guy, everybody liked him.

Top athletes retire young. As I understand, George retired to a car dealership that didn’t do well and his Moonhole house fell in arrears. Wealth was a Moonhole requirement. Some other complication may also have arisen between Tom and George – that impression from the little that Old Tom told me. King Tom got his way, according to his own reasoning, which would have been honest to himself. George was out. And his Moonhole House, Ravine House, remained abandoned for over a decade before the family offered it to me.

I had wandered through many of the houses but didn’t know Ravine House. I got directions and visited the house several times while I considered the family’s offer, to wit, that it would be mine until sold (and the house was in ruin and was not for sale). I could work on the part I was using but I couldn’t start breaking out walls or anything. My first visit was cursory. The house was so dilapidated and overgrown that I couldn’t get to much of it. My second visit, I brought a cutlass and began cutting my way into the part of the house that I came to call the High Tower, first hacking my way in through the open bathroom, then clearing the stone stairs leading down to the rest of the house.

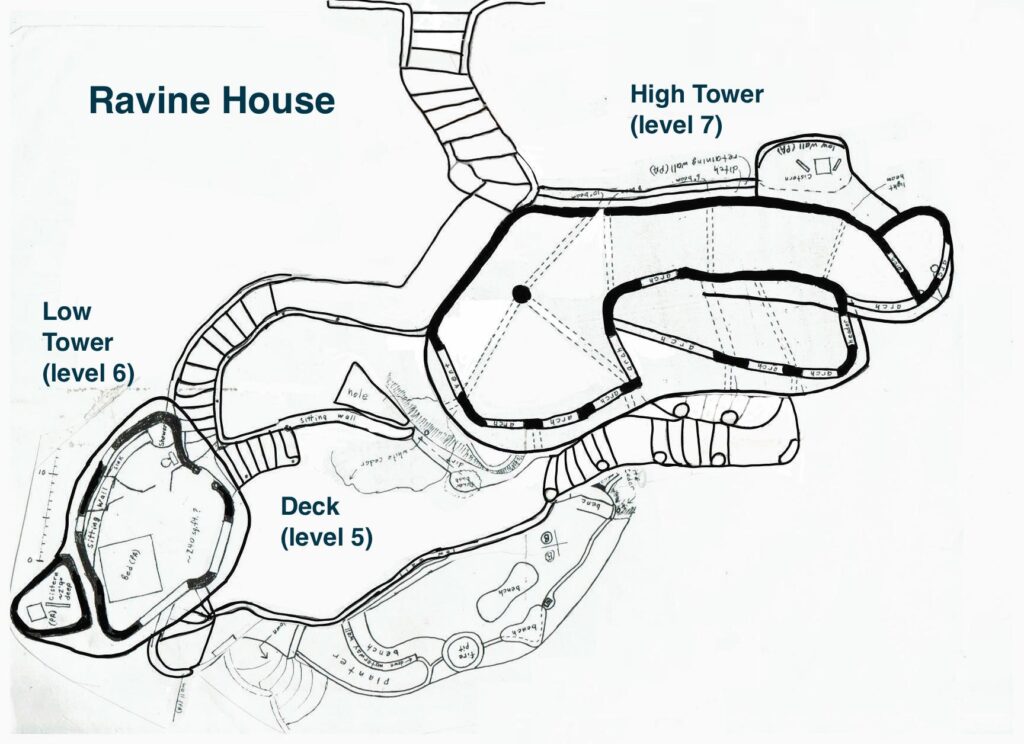

Most of the Moonhole houses were built either behind the beach just inside the gate or along the rocky ridge of the peninsula. Ravine House rose seven stories from the sea on the southern side of the peninsula, a quarter mile from the gate along the trail known as the Fisherman’s Highway. The Fisherman’s Highway was about a hundred feet above the sea, just above the height of Ravine House. All that could be seen of the house from the trail was the roof of the High Tower and the steps leading down past the face of the Low Tower, then out of sight as they wound into the five levels below.

The High Tower had a bedroom and what I called a study, backed by a corridor that I called the Cave, leading to the open-air bathroom, a classic Moonhole “loo with a view.” The bedroom had three large windows overlooking the lower levels of the house, in front of which stood a desk. There were books all over the place, hundreds of books, mostly paperback. Lying on the desk, as if meant for me to find, was Arthur C. Clarke’s “Fountains of Paradise”, which I hadn’t read.

I accepted the family’s offer. I was cruising aboard my little yacht and only spent about half of my time at Bequia. But while at Bequia, I spent about half of my time at the house. My joke came to be that after three or four days at the house I got tired of the mosquitoes. Then after three or four days aboard in the bay I got tired of the rolling. I frequently invited people I met in the harbor to the house and invited them to bring their laundry – the house had five cisterns that I knew of and another was later discovered. Often we would stop by Jean at Roundhouse on our way in. Sometimes I showed them through the buildings within Moon Hole Arch. But Ravine house was a complete experience in itself. Almost everyone was blown away. I could tell people what Moonhole was like but that didn’t do it justice. Whatever you’d seen, Moonhole was a new experience.

Chess was synonymous with a visit to Tom. Over the years we played many games. That alone was a great pleasure and commanded our attention during each contest. But we talked before, between, and after and I came to know Tom Johnston as told by Tom Johnston. I don’t generally crosscheck people’s stories about themselves except by accident. If you want to tell me that you are a doctor, lawyer or Indian chief, that’s fine by me unless it matters. So, most of what I know about Tom Johnston is his version, told by Old Tom himself. His mother was a noted horsewoman. Tom left home for a life of his own at twelve or thirteen. He got into prestigious Deerfield prep school against all odds. He thence went to Princeton. At both Deerfield and Princeton, he was a star athlete. In WW II he was a US Navy officer, generally in charge. Of his rise in the advertising business, what I heard was his final status, at the top. In Old Tom’s telling, it was all a matter of him basically taking what he wanted, whatever he was determined to have or determined to be. Our memories of our past evolve into legend. How true are they? Or one might simply approximate from results – in Tom’s case, Moonhole. He was King and his ways prevailed.

But Tom didn’t actually build Moonhole. There was Gladys, who oversaw everything that wasn’t construction. And it was the people of Paget Farm who actually did the building, gardening and domestic service.

By my time, Moonhole’s glory days had passed. Gladys was gone, the building had stopped and most of Old Tom’s Princeton mates were dying or dead. Their offspring were entertained by technology and didn’t understand the charm of a place where cell phones didn’t work. Only a handful of the houses were inhabited, the others seldom visited. When Moonholers visiting their house asked who was in Ravine House, Jim told them it was a Colorado hippie. That was cool at the time. Moonhole, to us, was about nature and freedom.

Meanwhile back at Ravine House, though I had no intention of using most of the house I was cleaning up and fixing up a little here and there. The place was a mess. It was a ruin with chunks of concrete falling from the ceilings. At least half of the books were damaged or eaten beyond reading, so I burned those without looking at titles. Over the years the house’s drains had clogged and much topsoil had accumulated on the stone stairs and around clogged drains on the concrete decks, which I scooped up for gardening. The worst of it was all of the cushions, (the house had lots of stone furniture so there were lots of cushions). Mattresses and mosquito nets had been stored around the house for a decade and were now full of life and lizard eggs. And water had gotten to much of it.

I even hired a gardener, Rudy, who also worked for Jean. Rudy worked half a day at my house twice a week. The house already had a lime tree and I soon had spinach and papaya. Rudy also planted a mango tree and an avocado tree, both of which he had grown to knee high at home.

There was a back trail to the house a couple of hundred feet further down the Fisherman’s Highway from the main entrance, entirely unused, disappearing into a tangle of bush, which joined the house on a large concrete deck at level three. Shortly before this back trail turned towards the house it branched to the right into a thicket of scrub trees atop a rocky point sloping steeply to the sea, the west point of the ravine. Beyond the trees a trail was carved in the conglomerate rock down the side of the point away from the house ending in steps and handholds cut into the nearly vertical last several meters down to a natural rock shelf barely above the water, a meter or so wide, wrapping the rocky point back towards the house. Rounding the point, the house came into view and the shelf ended at the edge of the blowhole that sometimes erupted from a small cavern. Spanning the blowhole were the remains of a minimal footbridge to a huge boulder on the other side, which rejoined the house at its lowest corner, at the bottom of the steps winding down from the top of the house. They terminated in a kind of delta of steps, fanning out as they spread onto the bottom deck of the house.

The lowest two levels of the house were spacious bedroom suites spanning the ravine with wooden floors. They were in dangerous condition and I explored them cautiously. From the third floor up, the structure was concrete and rock. Large planters were incorporated along the walls and steps and there were stone benches and seats all over, which once had cushions during times when the house was occupied. Handrails along the stairway were whale ribs. There was a bar fronted by a whale jawbone and whale vertebrae were used for stools. However one regards Bequia’s indigenous whaling, Moonhole bought the one part of the whale that the islanders didn’t use, its bones. The houses also incorporated a great number of large, heavy glass fishing floats netted in rope, which go adrift on the other side of the Atlantic and land in these islands. Tom bought all of those that he could plus driftwood, hawsers and whatnot.

No roads, no straight lines, kerosene lanterns, loos with a view, planted rock pools inside and outside the houses, houses and roofs built around trees, roofs that make stalactites, walls that were largely huge frames around the view, these are Moonhole qualities. The themes of the individual houses followed the lay of the land in whatever fanciful design came to Tom’s mind. Call that inscrutable. I came to my own interpretations. The stone stairway wandering downward through Ravine House was a stream that was usually dry, a winding descent through the house connecting the staggered levels. The stairway ran like a river when it rained. After such rains the decks were big pools heavy in water. So I saw clearing the drains and keeping them clear as important.

All of the ponds and all of the cisterns had tiny fish. Where the Fisherman’s Highway trail began to climb away from the end of Moonhole Beach, at an intersection of trails, was a pool in the shadow of trees that I took to have some sort of magic, and which was the breeding pond for most of the fish now swimming the many cisterns and ponds with which Tom blessed Moonhole houses… not that I don’t suspect Gladys hand in the matter. Fish were in all the tanks and pools, drinking water and all — otherwise, mosquitoes. Someone asked Tom if the water was safe to drink. He said he’d been drinking it for over thirty years. But that is a tourist question – everyone on Bequia drank cistern water.

Between games, Tom once told of the government getting on him for building houses without submitting plans. Tom invited the guy in charge to Moonhole, showed him around and asked, “How do you draw a plan of this?” It was point well taken and I suppose Tom’s commanding ways and a certain kind of charisma played a part, but Moonhole itself was the exhibit,

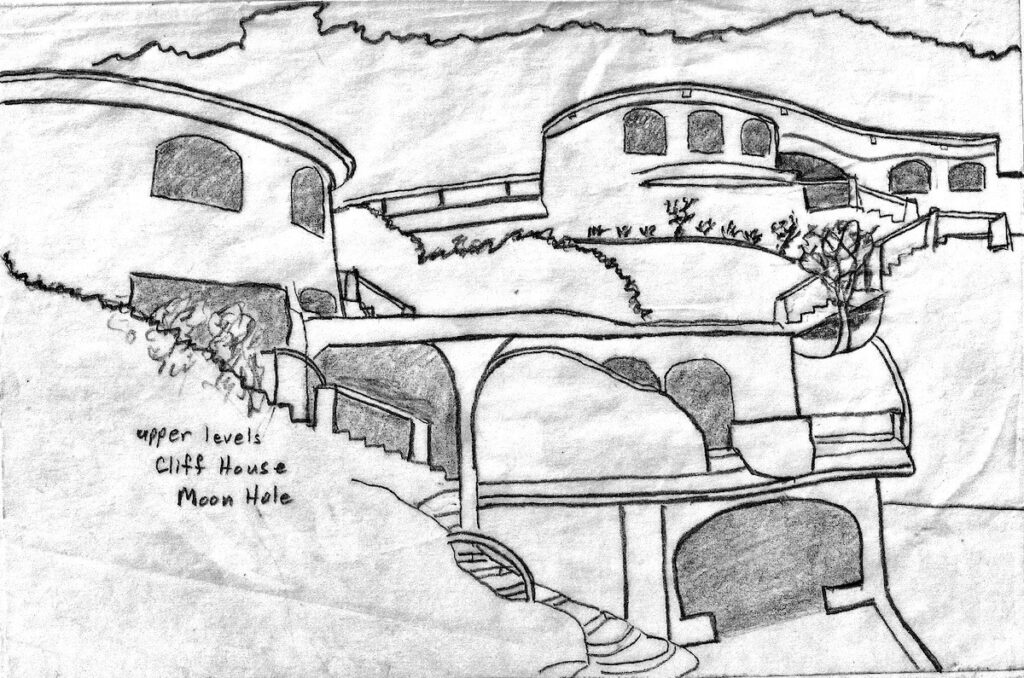

One can draw the resulting structure, as I did, but not with precision. I measured the top of the walls, the bottom of the walls lie roughly beneath. The wander of the walls was a function of topography (particularly in my house) and fanciful imagination.

Here’s an example, my rendering of the High Tower, the Low Tower and the deck between, also showing the stairway up to the Fisherman’s Highway behind and above the house.

The High Tower consisted of a large bedroom with a pillar and the Cave leading to the loo with a view, all on one level… well, far from level. A sloping rock face of the ravine extended into the Cave from halfway up the wall to halfway across its floor. The Cave had bats. A half level below the bedroom is the Study, where I hung my hanging chair, in which I somet6imes slept. From the Study, steps lead down to the deck at level five. Halfway down the stairs was a landing shaded by a small white cedar tree, where I did my laundry and had my showers.

Across the level-five deck and up the steps is the Low Tower, one room about the size of High Tower’s bedroom, with two large windows looking down the ravine and out across the water. I rigged awnings, both as shade and to catch the breeze.

A narrow back door opened onto a face of conglomerate rock – the ground level was about roof high. I chiseled steps in the wall up to beside the top of the substantial cistern nested beside the Tower. From there I cut a curved path into the bush, where I cleared an area that I called the Living Room, which had a nice white cedar from which to hang my chair. The extending part of level four is lightly drawn at the bottom… and there were three levels below.

My first occupancy was in the High Tower, which I had cleared, cleaned, and made usable. There was a bed with a mosquito net in the center of the bedroom, my hanging chair in the study, and a cave-like walkway to the loo with a view. Both the bedroom and study had a desk. The floor of the study was dished and sloping such that the four legs of its desk, each cut to a different length, only fit the floor in one place, in front of a window. The top cistern behind the tower was unusable due to leaves from a toxic tree collecting on its catchment. So I set up a garden hose siphon from the cistern under the loo. The hose ran down to a landing halfway down the steps. A white cedar tree beside the landing provided good shade. That’s where I had my showers, did my laundry and filled buckets to recharge the loo. The High Tower was my campsite for about a year.

There is no way to close a Moonhole house, much less lock it. There was a long shelf in the Cave where I laid out my tools –cutlass, file and gloves, hammer and chisel, saws, and such. On the desk In the Study I had an ashtray with loose change in it. And there was a clever spot in the desk where I hid a small transistor radio. When I returned after a several week sail, I found the dollars and quarters had been taken from the ashtray and the radio was gone. My tools hadn’t been touched. Fair enough. Now I knew.

Then I moved to the Low Tower, which had been a real job to clean up. The drainage ditch in back of the Tower had clogged with all sorts of trash. Water off the hillside had been running into the room depositing deep mud and ruining much of what had been stored there.

The Low Tower had a better breeze. It also had a backyard. The back door opened onto a conglomerate face into which I cut steps up to the bush. Then I cut a short trail to a small clearing I made, where my hanging chair now hung. The area was a shallow ’v’ across the hillside, a natural rain runoff from the Fisherman’s Highway. Though only thirty feet from the trails and house, the spot was isolated by dense bush. I called it “the living room”.

I built a loose rock retaining wall across the bottom of the clearing and backfilled it with soil from the back of the clearing, decreasing its slope – and uncovering several meter-size black rocks that I rearranged as “lounging boulders”. The bush at the downhill side of the clearing was low enough to see the sea over the top and allow some breeze in. The Living Room was a nice place to hang.

I reckoned the retaining wall and its backfill would retain more than its share of rain runoff from the hillside and planted a well-started mango tree near one end of the wall near the entry to the clearing. And I planted the avocado tree Rudy had started in a place that he approved, outside the clearing near the lime tree. I also had spinach growing up walls and papaya that got window high in front of the Low Tower – all you have to do to grow papaya is throw the seeds out the window. And it grows fast.

So it went for several years, hanging in my house, showing it to others, hanging with Jean at Roundhouse, with Jim and Sheena at their house, chess with Tom, hiking the Fisherman’s Highway to West End (carrying a cutlass to clear the seldom used trail), with several-month absences for my sailing lifestyle.

Jean and I had talked about what “mine until sold” might mean. Jean, a real estate appraiser, assured me that nobody was going to buy the house. The house was in such bad condition that it was worth the price of the land it sat on less demolition costs. Further, he thought, even if some man fell in love with the idea, his wife would emphatically say “No!”

Then along came the Brewers.

Charles and Cornelia Brewer were retired. Charles was in his late seventies. He had been an architecture professor and a famous architect in New England. After retiring, they had bought a yacht and sailed around the world. Now he wanted to build a house in Moonhole, what he called his “last new life”. Tom had tentatively agreed. Charles drew up his plans and brought a model for Tom to approve. The Brewers were staying with Jean at Roundhouse. Tom gave them a verbal approval. Verbal was as good as you got out of Tom, but his word was good. However, some years earlier Tom had asked some of the homeowners to set up a trust to protect his creation after his death. The time had now come for the trustees to tell Tom that he was no longer actually King of Moonhole. And they told the Brewers that it had been decided not to sell any more land.

While the Brewers were lingering at Roundhouse considering their options, I offered to show them “my” house. By the time they had wandered Ravine House from top to bottom and back up again, Charles was in love with it. Within days they called a meeting with Jean and me to announce that they intended to buy Ravine House. Furthermore, they would give me the Low Tower, the small portion of the house that I was using, as my own. While that might sound a bit fantastic, there were good reasons. We had all become friends right off the bat and shared a common love for Moonhole, as each of us perceived it. And the Brewers intended to be commuters, sharing their time between Moonhole and their place in Vermont, whereas I stayed in the Grenadines. Having me in the house would be good security.

The Brewers began negotiating to buy Ravine House. That went slowly. The homeowners were stonewalling them. Then, as I understand, a homeowner who had just learned of the proposal said to the other homeowners, “Do you know who Charles Brewer is?” They saw that financially and socially the Brewers were one of them. But then, out of the blue, George Stark made a move to reclaim Ravine House. The Brewers were in with the homeowners, but ownership of the house was now called into question.

Charles wanted to get started. His attorney said that working on the house might strengthen their case, but for him not to invest more money than he could afford to lose.

One of the things that had been decided was that my unit should be entirely autonomous. The entry to the Low Tower was across the stairway running down into the house and across a deck from the entrance to the High Tower, so that part was a natural. The Low Tower had its own cistern. What it lacked was its own loo-with-a-view and associated leech field. Charles offered to pay for that, and I hired a crew to put it in while they continued the purchase process. I hired Rudy, his half-brother Ambrose, and an energetic man named Felix. We had the new system nearly complete when the Brewers returned to take possession. The Brewers stayed with Jean at Roundhouse for the first part of their remodeling, but on the day they arrived Charles had Moonhole workers bring in a large canvas bag from which he took a sledge hammer and started breaking a hole in the wall between the Cave and the Study. In the following weeks, he and his crew broke out walls under the windows to make arched doorways and more windows. As Leroy, a long time Moonhole employee, and I watched, Leroy commented, “Do they know that it rains here?” But meanwhile the Brewers were having a sort of tent built over their bed, which could be lowered for inclement weather. Charles took my crew of three, hired about six other workers and they started building.

I continued to putter around in my part, now thinking in terms of a permanent residence instead of a camp sight. But I was already pretty well set up. The Low Tower was a big all-purpose room in which I had a bed, desk, and a miniature galley. And out the back door was the trail to my open air “living room”.

My galley was minimal, barely enough. When I’d first been given the house, Jean gave me an alcohol fondue burner so that I could at least make coffee. Aluminum flashing from a defunct refrigerator made a cylindrical shroud that held two large stainless steel cups stacked above the burner. The lower cup cooked while the upper cup warned whatever was next. A door to tend the burner and cups opened with a piano hinge made by bending alternate tabs of the flashing over a length of stainless wire. For the time, I had the only electricity in the house, a small solar panel charging a small battery, which gave me about an hour of reading/writing time per night from a five-watt halogen light. Kerosene lanterns provided general lighting. Not having a refrigerator to protect my food from ants, I kept it in small buckets hung from the ceiling with string. For hand-washing my laundry, I had an old-fashioned hand-crank wringer. In a minimal way, I was set.

When the Brewers first stayed at Roundhouse. While hanging out with them on the evening of their return, Jean and I put them to task as to whether or not they were, in fact, Moonhole types… as we saw things. That is, what Jim and Sheena and Jean and I saw Moonhole life to be, which was a bit of a variable even among us. The basic test was whether Charles Brewer could get in a hammock and just lie there. He kind of thought that maybe he could. That proved not to be the case. Nor Corn for that matter. She was Charles’ “facilitator”. Her job was to find any and everything that Charles needed and get it to the site, usually within a day or two. Somewhere along the line I said something to them about vacations and Corn snorted, “We’ve never taken a vacation.” So, you can see why Jean and I were concerned.

Soon after the Brewers were in residence, Sophie, one of the two very rich sisters who owned Long Point, a rambling collection of Moonhole structures well beyond the rest of the houses, came for one of her brief visits. Charles and Cornelia, the new Moonholers, were invited to her traditional Moonhole sunset gathering. Charles said that since I was now one of the homeowners, I should come too. So off we went. Charles was carrying his Techna flashlight and a carved Brazil wood walking stick and was dressed like a fashionable architect in the tropics. I carried a kerosene lantern, a bamboo stick and was dressed like I dress. Charles jokingly introduced me as Diogenes (which I took as a compliment). But I needn’t have worried about seeming strange. Sophie introduced us to the guests she had brought. They were an abbot, a monk and a nun from a convent in Arizona that she supports, an Argentinean filmmaker, her personal architect, and an artist who carved mazes in corn fields with a weed whacker. Sophie’s daughter was also there with a friend, but they were laying low. It was an interesting affair.

Diogenes indeed! Diogenes allegedly lived in a barrel. In addition to all the furnishings I’ve already mentioned, the Low Tower now had a flush toilet! When the system had been completed and the toilet installed, I handed out written invitations to Jean, the Brewers, and the family inviting them to “A Flushing” at Ravine House to inaugurate the system. Even Old Tom came, helped along by Jim, resting along the way. During the proceedings Old King Tom took the throne and pontificated.

I was spending most of my time at Bequia now, most of it at Moonhole. Even as I was puttering around on my mini-domain, I was building my first crazy craft for Bequia Easter Regatta 2001. Its framework was small bamboo ribs and stingers with their ends joined by sleeves of dead garden hose, abundant in the ruins of the house.

My former crew, Rudy, Ambrose, and Felix were happily employed, along with Charles’ additional crew. The Moonhole building style, sans power machinery, is labor intensive. Sand, cement, and steel had to be carried a quarter mile from the end of the road outside the gate. Stones for building had to be gathered from offsite.

Felix got a solo job on level four carving out a cave-like alcove from the structural conglomerate ravine wall with a heavy hammer and chisel. Felix often told me how much he liked coming to work, to the peace and quiet of Moonhole. He didn’t mind the work at all, whether chipping a hollow into the beautiful conglomerate (for it was beautiful) or hauling in heavy bags of sand from the gate along a shady trail, which was a pleasure to walk. The workers liked working here. And the Brewers had payday and cold beer for them every Friday afternoon.

Three women were contracted to break aggregate for concrete, Rudy’s mother, an aunt and a cousin. Rudy’s mother had made aggregate for Ravine House during its original construction while Rudy, a kid, played on the small beach that was once at the foot of the ravine. These women were professionals – it was not a menial job to them. They chose their work location on a shady level spot near the house, several workers were assigned to bring them the right kind of rocks, they came in the morning and they went home at noon. A big pile of properly sized aggregate grew quickly beneath them.

The Brewers and I were living quite nicely together, close neighbors but separate.

Charles was energetically converting Tom’s art into his architecture as Cornelia did daily runs by ferry to St. Vincent, where she scoured Kingstown and beyond for all of the very particular things that Charles wanted for the house – brass faucets of a certain design, for instance. He was the noted architect, she was his facilitator. Their energy and the progress of their project were impressive to witness.

Were the Brewers “Moonhole”? By wealth, culture and status, they were right in there with the homeowners. In terms of building, they were right in there with Tom Johnston… well, not exactly. According to Jean, Tom would go to the site in the morning, tell his foreman and crew what he wanted, then spend the day in his hammock or doing whale bone scrimshaw. Charles was on site working, in charge, hands-on. Charles Brewer had a long resume of prestigious architecture, plus having been a college professor of architecture.

Old Tom, Jim and Sheena, Jean and I lived what each of us imagined the Moonhole philosophy – its fundamentals being freedom, nature and being isolated from the rat-race… primitive, minimal… slow?

As Charles charged forward, toward the amazing house he envisioned, I puttered away on the small part that was mine, my interpretation of Moonhole, my variations on Tom’s themes.

When the house had been all mine, I had used the loo with a view in the High Tower and showering on the steps. Now my autonomous toilet had been installed – indoors – without a view.

The sewer line from the toilet ran out from the seaward point of the oblong Low Tower and across a steep face of conglomerate rock in which a trench had been cut. I picked the conglomerate rock back farther to make a narrow trail to a spot where I picked an alcove into the hillside to fit a toilet, leaving wide shelves on either side. Then I built a waist-high wall across the front of the path, rich in interesting or colorful stones I had been gathering. Several little hide-e-holes, including one to keep the toilet paper dry, were built into the wall. Sitting on the throne, I was out of sight of the rest of the house. The view over the wall was of the waters and islands, with a blue sky above… usually. The colors of the conglomerate and the rock wall amid which I sat were pleasing, warm and varied colors. This was my Moonhole loo with a view.

My shower with a view was as good or better. The seaward point of the Tower perched on a large black rock with a smooth, dished top that sloped slightly towards the large space under the elevated Low Tower, which served as a large planter on the deck below. The rock was a perfect shower floor and the cistern was immediately above and behind – both shower and toilet were fed by siphon. As with the loo, it was out of view from the house but had a full view of the waters beyond.

A favorite project was replacing the rotted rail along the steps down from the Fisherman’s Highway. They had been beside the steps, like a guardrail. I replaced the posts with limbs bending inward over the steps and strung it with an anchor rode that was due to retire. It was a handhold you could pull on to aid the climb. Charles liked it too.

None of this holds a candle to what the Brewers were doing. They were doing what they knew, furiously building. I was doing my stuff, inventing and improvising.

The three of us were friends and frequently hung with friend Jean at Roundhouse. Moonhole was the center of our world… well, I still had Ambia, now anchored off Moonhole Beach. One day Old Tom and I were gazing out over the water and he said, ’That’s the prettiest little sailboat I’ve ever seen.” I agreed.

Then Charles and I had a different of opinion as to how the massive amount of wood, mostly hardwood, that made up the ruined lower levels of the house should be disposed of. Removing it by sea would be expensive and otherwise problematic. He wanted to burn it. I wanted to make terracing covered with earth to compost it. He let me do a small trial of the idea downslope of my house. But a realization was looming. The Brewer House would be the showpiece of a famous architect, with polished doors and bells. My small portion, the part of the house first seen coming down the entry stairs, was the showpiece of an eccentric artist — Tom Johnston, as interpreted by a man who had been introduced as Diogenes.

So, some months after the Brewers had moved in, I announced that I was giving back my portion of the house. Several days later all the employees stood outside my door as I gave away almost everything that was there, excluding two boxes that had to find stowage on my little yacht. Then I moved back aboard Ambia. Living aboard was what I had decided to do twenty years earlier and I still loved it.

But that didn’t end my Moonhole days. There was still Jean and his Full Moon parties. I house-sat for Jim and Sheena several times, and several times for Suzie, who took Tom’s Hill House after he died (much remodeled by Jean). And every so often I brought friends in to see “my” Moonhole house, to meet the Brewers and see their fanciful reconstruction. By the last time I did that, their saltwater swimming pool was in and we all had a swim.

Then Jean, ten years my senior, started getting tired climbing the sixty-four steps up to Roundhouse. He went to the US for state-of-the-art heart surgery, after which he expected to walk the beach telling the tale for another ten years. But the doctors killed him. During the operation he suffered strokes and somewhere along the line they gave him a medication that they should have tested on him first – which destroyed the ability of his bone marrow to make new blood cells. Jean spent two years on a downhill slide having his blood changed every six weeks, unable to see well enough to read, unable to speak well enough for conversation. He Finally made what he knew was his last visit to Roundhouse. And that was the last time I saw Jean.

Then came my last fling at Moonhole. I rented Roundhouse for a month to help with Jean’s expenses. My big brother, Rod, with a friend, and his son, Zach, with a friend, came to visit. And I threw a final Full Moon party, which I fancy was up to Jean’s standards – meaning good attendance by good people, mostly friends of his.

During my time at Ravine House, Jim had told curious homeowners that there was a friend-of-the-family Colorado hippie living in the abandoned Stark House. We were at the end of a Moonhole era. Once it was out in the open that Tom was no longer King, the foundation that had been set up for him began taking control. They were trying to stop Jim and Sheena from giving their Moonhole tours on the grounds of liability. And Tom, in setting up the trust, seemed to have forgotten Jim. I began to see it as rich people being greedy and covetous. Late in my stay in Ravine House, with the Brewers firmly established and accepted, a spokesmen of the foundation told me, very slowly and clearly so that I would understand, “We are looking for moneyed people.” I opted out in favor of my live-aboard lifestyle and came to prefer Carriacou over Bequia. I was mostly away during the long and nasty process of the Foundation throwing Jim and Sheena out of their home and business.

Charles Brewer’s Moonhole book makes no mention of me. No problem, his book. Still, he claims at least two of my adventures as his own, cutting a way into the long-abandoned house – which I had done years before the Brewers first saw the place, and he claimed the Flushing ceremony I’d staged when the autonomous toilet was commissioned – attended by Old Tom himself! Brewer says twice in his book, once in the text, once in a photo caption, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.”

I knew little about the homeowner takeover after King Tom died. I was down island. I knew that it was happening, then learned that Jim and Sheena had lost. I took it as a predictable example of “My lawyer can beat your lawyer.” But an element of the case spoken of in Brewer’s book mentions a document to the effect that if Jim stopped drinking he was in, if not he was out. Jim stopped drinking, for real – respect. This was while I was still there. Jim told me about it at the time. He said that Tom had became satisfied that Jim had in fact stopped. Then, during a visit, Tom had invited Jim to join him for a beer. Jim said, “Are you trying to trick me.?” Tom replied, “No. A beer isn’t drinking.” Jim mentioned the agreement. Tom took it out and wrote “Null and void” across it. According to Brewer’s account, that had been offered as evidence that Tom had disinherited Jim. I don’t think that piece of evidence made the difference. The homeowners were intent on evicting Jim and Sheena and that is what they did.

Then Jim and Sheena did an admirable job of making a new life for themselves on St Vincent.

© 2022

6 Responses

Sorry that we never met. My wife, two young sons and lived at Moonhole for most of 1992, the year Gladys died. Gladys was my mother’s only sibling. She and Tom, King Tom as you rightly call him, visited us in the States every year as I grew up. My first trip to Bequia was in 1973 while in college. “Blowhole”, which was the original name for Stark Ravine, was recently finished and owned by British gent with a lovely South American girlfriend. My wife and I returned in 1981 but began our love affair with Bequia in 1988 when I met the whalers and decided to make a film about them, “The Wind That Blows”, which I finally finished in 2012 . Anyhow, all my life I thought of Tom as an eccentric but joyful person but after we witnessed how King Tom ruled Moonhole and how he treated Gladys during her last days I realized he was quite mad found it incredibly painful to look after him any longer. When Jim (my half cousin) and Sheena moved to Moonhole in the fall of ’92 we vacated as quickly as possible. All the understandings we had reached with Tom while caring for him and Gladys at our home in New Jersey and in Bequia were now “null and void”. I testified at the trial in 2008 on Jim’s behalf but I believe the die and already been cast and the lawyers on both sides had agreed on the outcome.

Ahoy Tom !

Thank you for the additional background.

A longtime Moonhole homeowner took exception to some of the story. He referred to it as “false narrative” and “fairy tales” and said that I didn’t tell the whole story. Indeed, I only told my personal experience. The whole Moonhole story would fill a book – which I am not qualified to write.

Does anyone have more history they would like to add?

All comments are welcome on any of the stories on this site.

One Love, One Man

I remember hearing about Tom Weston and his film project from Gladys after I started coming to Moonhole in 1969. My father built a house there in 1973. The house went to ruin after my parents died, and neither I nor my siblings were interested in continuing my father’s Johnstonian dream. My siblings are not the “get away” type, and I am more connected to the Bequia locals than White Supremists (not to be confused with White Supremacists). I’m more interested in being part of the Indigenous culture.

We sold our house to the Hoovers a few years ago, and they’re rebuilding it. Their project is close to finished (https://twitter.com/MoondanceBequia) and I keep in touch with them. I’ll be speaking with Bo Hoover this week.

I’m now finishing a book on my father’s work as an architectural photographer. I’m closing the book with a chapter on my father’s Moonhole house. If you’d like, I’ll send you the manuscript asking only that you give me your comments.

My book is bigger than Moonhole, as I focus on Moonhole’s cultural and architectural context. That context is useful because Moonhole meant something deeply personal to all those involved. The intrigue gets in the way of seeing where the people came from ,and what influences formed them.

— Lincoln Stoller (you can email me at LS@mindstrengthbalance.com)

Hi, did you no Sheena Johnstone. She married Jim? She’s my auntie

Ahoy G Gleadhill

Yes, as told in the story. Jim and Sheen, Jean Possion of Roundhouse and old King Tom were friends of the first order, my Moonhole family. I hope that comes through clearly in the telling. My Moonhole adventure is fondly remembered.

Hi Hutch,

Thanks for the amazing story! We sailed to Bequia years ago and could only stay a short time but vowed to come back. We finally made it! We’re spending about 5 weeks here looking at houses and properties and we were super excited to find one for sale in Moonhole -“The St Vincent House.” So excited that we decided to rent it for a few weeks to see if we would like it. We started exchanging emails with the Carroll the “Rental Coordinator” located in New Orleans and were, less than warmly received I’ll say, and a few days later we’re off the idea all together. We asked for a tour of the house prior to renting and she was very unhappy about it to say the least. In the end, and after reading the by laws that she sent for Moon Hole, we’ve decided it’s a miracle any of them still exist at all—it’s crazy restrictive, the “board” has all the control and could quite literally lock out any chance of you ever renting or selling your own house—if you were lucky enough to get approved to buy it in the first place; so we ditched the idea. What a shame~.there are loads of folks that would love to keep the dream going but the person we dealt with threw up so many random roadblocks to success, we could only conclude that she was trying to exclude us before ever even meeting us. Any insights into why the current owners would put up with this?